10) Endometrium

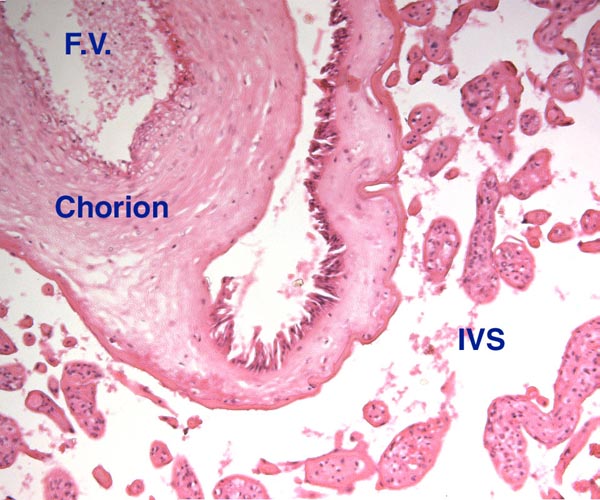

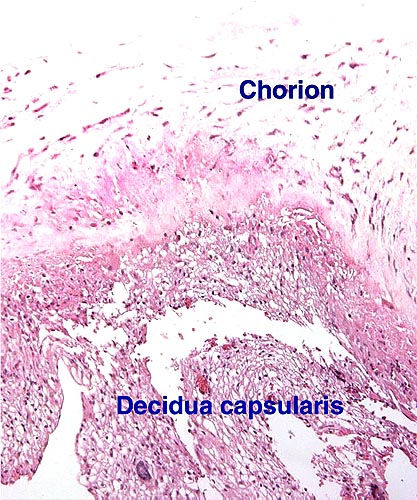

There is little decidua shed with the delivered placenta. Moreover, Walls (1939) found virtually no decidua vera, and only very little deciduas capsularis in his first trimester specimen. Little decidual tissue, intermixed with some trophoblast, is found in the delivered placenta.

11) Various features

No other significant observations were made.

12) Endocrinology

Ovarian cycles and a pregnancy were examined by fecal steroid analysis only once (Patzl, et al., 1998). These investigators found the onset of ovarian cyclic activity after pregnancy to occur within 4-11 weeks. The pregnancy lasted 184 days. The average length of ovarian cycles was 51 days. Progestogens rose above the cyclic luteal activity in the second half of pregnancy and were 20 times higher during the week before parturition. Estrogens rose significantly in the last third of gestation and, especially, shortly before birth.

A detailed hormonal study of cycles in six animals and study of pregnancy diagnosis comes from the doctoral work of Nicole Schauerte (2005). Cycles were not seasonal and polyestrous with slight vaginal bleeding occurring in the pro-estrus. Ultrasonic determination of pregnancy was also documented.

Additional observations on the endometrium by Becher (1931) are useful. In his large study of pregnant and nonpregnant uteri of four-toed tamanduas, Becher described the cyclical change of the endometrium. It had many similarities with human endometrium, and periods of estrus were described with marked secretion of mucus from the vagina. In the later stages of the endometrial cycle, the photographs suggest that there is a decidua-like change of the endometrial stroma. Much extravasation was reported in later stages of the cycle and in early pregnancy, Becher described a thick decidua. He also correlated the endometrial changes with the state of ovarian activity and described the appearance of the corpus luteum.

13) Genetics

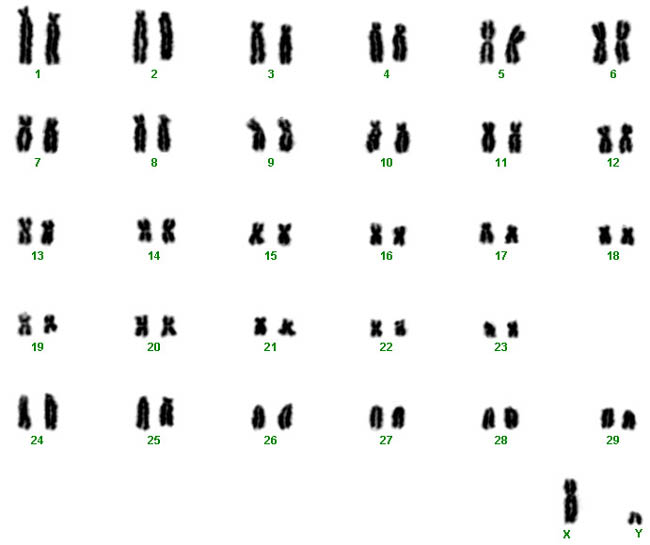

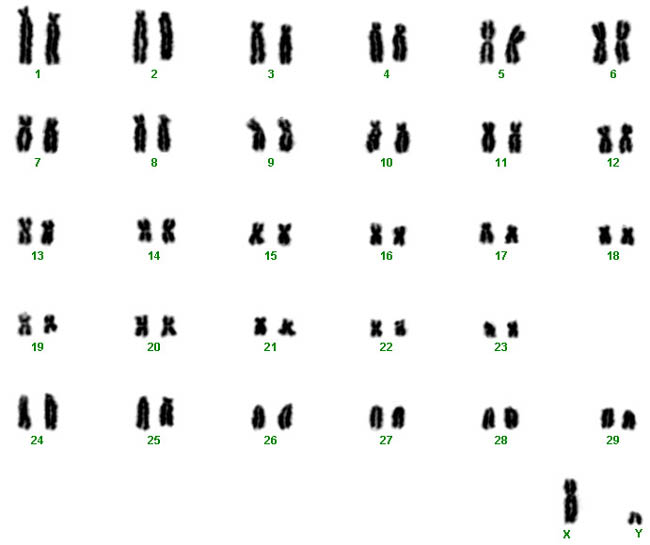

Giant anteaters have 60 chromosomes (Hsu, 1965). We can confirm this from our own study of four animals. No other chromosomal studies have been published. Garcia et al. (2005) studied and characterized six microsatellite markers that may become useful for studies of population and paternity.

|

Karyotype of male giant anteater from CRES.

|

14) Immunology

There are no published reports.

15) Pathological features

A small number of giant anteaters have been autopsied and only a few specific lesions were identified. Baskin et al. (1977) found infection with Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, presumably from contamination of feed by rats or pigeons. Diniz et al. (1995) identified digestive disorders as most prominent features, with many other systemic diseases being less common (infection, nutritional, respiratory, etc.). Parasites of one kind or another were found in 48% of fecal samples. Griner (1983) listed trauma as a major problem in captivity (tapir-induced neonatal mortality), and arteriosclerosis.

RNA viruses (Picobirnavirus) were found in the fecal study by Haga et al. (1999). Labruna et al. (2002) found numerous ticks (Amblyomma sp. etc.) on these animals as well as many other species from Parana and Mato Grosso. Freitas et al. (2006) recovered Eimeria species in giant anteaters.

Coke et al. (2002) documented gastric perforation (Entameba and Acanthamoeba spp.) in an animal with peritonitis (after perforation) and cardiac myopathy (dilatation).

16) Physiologic data

There are no reports to my knowledge.

17) Other resources

Fibroblast cell strains of four animals are available from the "Frozen Zoo" at CRES of the San Diego Zoo by contacting Dr. Oliver Ryder at oryder@ucsd.edu.

18) Additional remarks and needs for future studies

The contribution by Becher (1931) on Tamandua tetradactyla is important in this context. In the first place, Becher had an unusually large material of pregnant and nonpregnant uteri available. But, more importantly, he described the material as having been well fixed for histologic studies. In addition, he had several stages of fetal/placental development available that provide more insight than the study of one particular stage. He pointed out that this is perhaps the reason why his findings differ in many ways from the interpretation of Wislocki's single specimen of a two-toed anteater (1928).

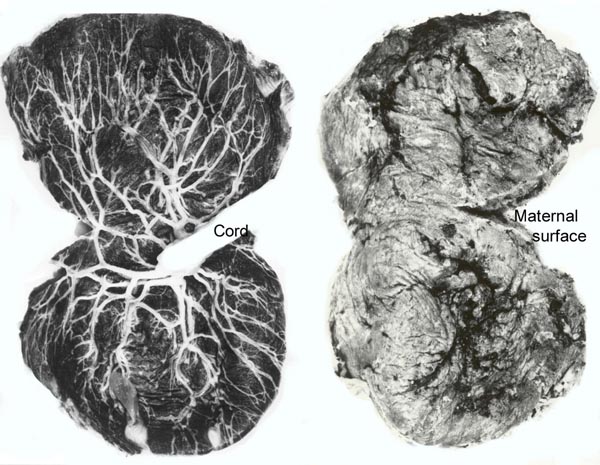

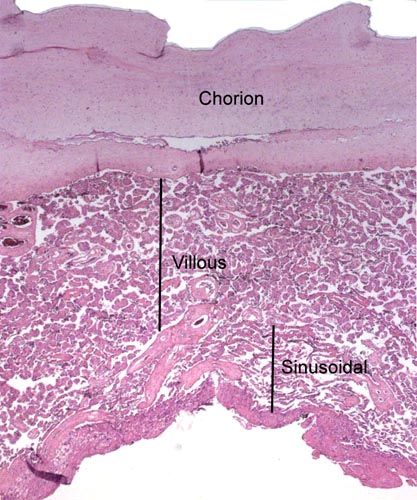

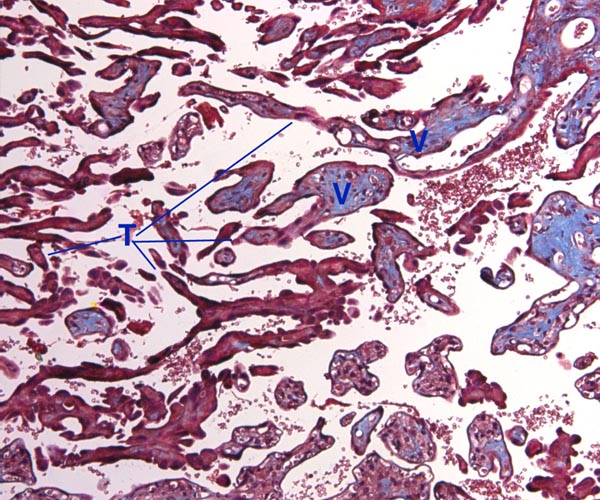

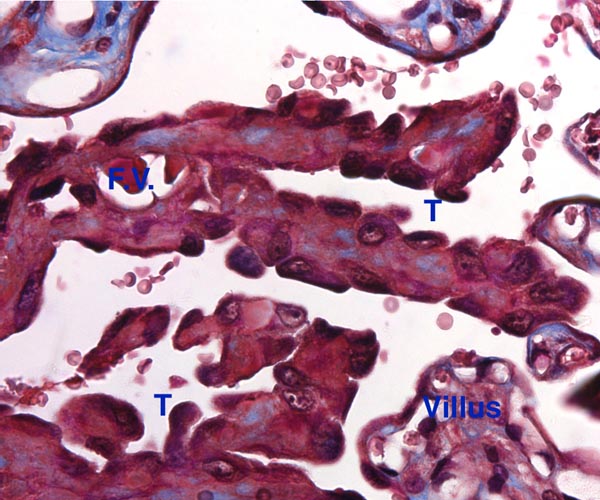

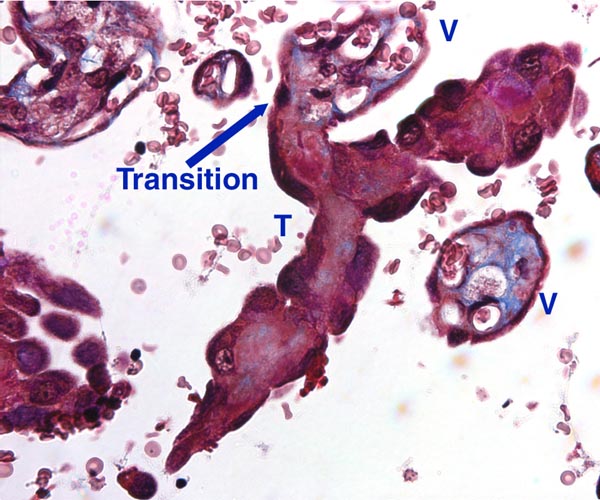

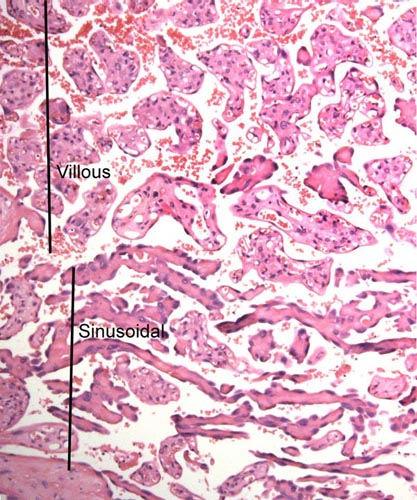

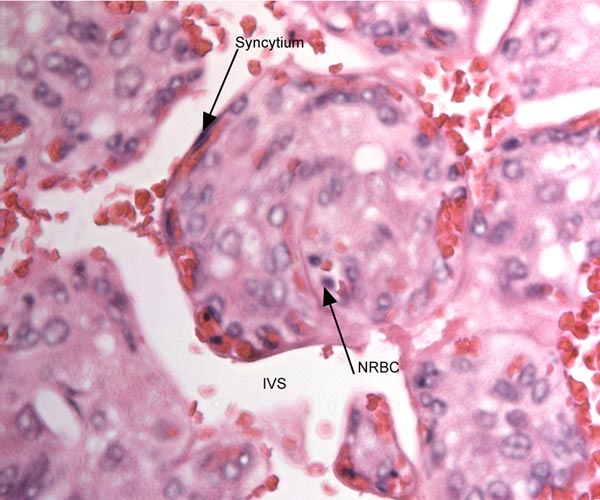

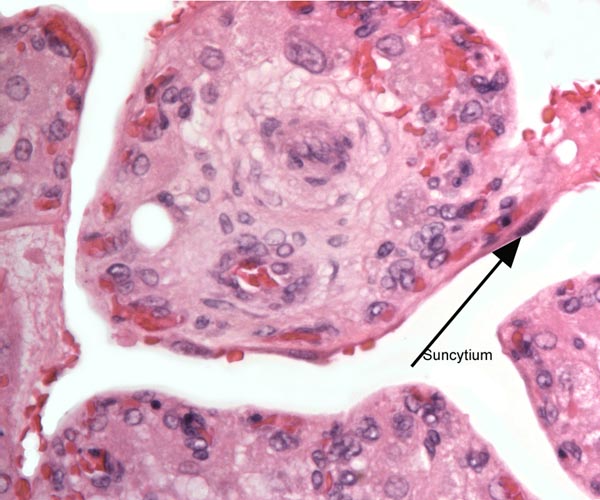

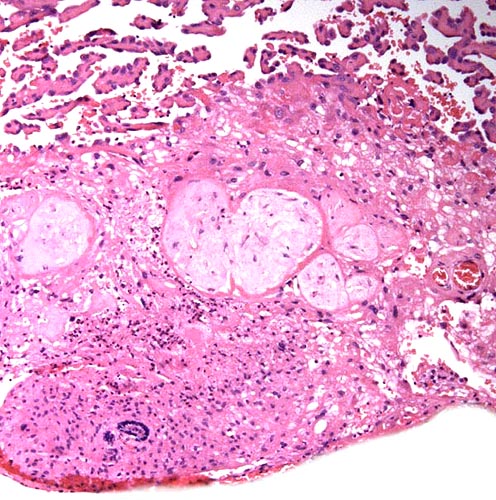

I will summarize some salient conclusions from this related species of anteater that was studied by Becher. These remarks are probably equally applicable to the placenta of the giant anteater. The placenta was always implanted at the fundus and, with advancing gestation, the uterine wall became very thin in the region of nidation. In the fundus, a vascular network developed in the musculature that was visible externally. Becher spoke of a "corpus cavernosum". The maternal surface of the placenta had a finely lobulated appearance. No yolk sac and no allantois were observed, even in the earliest stages of pregnancy (that is quite different from what Enders described for the armadillo). The umbilical cord inserted centrally and the lengths of some cords were given for immature stages. Becher and other observers reported that the periphery of the placental disk has a trough. Perhaps this led to the suggestion that it has a bell shape. The study presented an interesting flat section through the organ. This displayed the "mesodermal villi" (his choice of words) to be connected to one another by the solid trophoblastic trabeculae. These, Becher found (in contrast to Wislocki) are composed of large cytotrophoblast and contain no connective tissue. He found these sheets of trabeculae to become hyalinized toward term and interpreted them not to become zones of possible future expansion of the villous structures. Their plump cells have no microvillous surface. Most interesting to me is his observation that the placenta shed in the "muscular" (!) cavernous zone (not in the decidua).

There is much work to be done on the nature of this peripheral zone of the xenarthran placentas. Most important will be the identification (maternal vs. fetal) of the individual trabecular elements by genetic means. Electronmicroscopy will be mandatory also to better understand the contribution of the trabeculae to the placental development and its function.

Acknowledgement

Most animal photographs of this book come from the Zoological Society of San Diego. I appreciate their help and that of the pathologists at the San Diego Zoo.

References

Baskin, G.B., Montali, R.J., Bush, M., Quan, T.J. and Smith, E.: Yersiniosis in captive exotic mammals. J. Amer. Vet. Med. Assoc. 171:908-912, 1977.

Becher, H.: Placenta und Uterusschleimhaut von Tamandua tetradactyla (Myrmecophaga). Gegenbauers Morphol. Jahrb. 67:381-458, 1931.

Coke, R.L., Carpenter, J.W., Aboellail, T., Armbrust, L. And Isaza, R.: Dilated cardiomyopathy and amebic gastritis in a giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla). J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 33:272-279, 2002.

Diniz, L.S., Costa, E.O. and Oliveira, P.M.: Clinical disorders observed in anteaters (Myrmecophagidae, Edentata) in captivity. Vet. Res. Commun. 19:409-415, 1995.

Enders, A.C.: Development and structure of the villous haemochorial placenta of the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus). J. Anat. 94:34-45, 1960.

Freitas, F.L., Almeida Kde, S., Zanetti, A.S., do Nascimento, A.A., Machado, C.L. and Machado, R.Z.: Species of the genus Eimeria(Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) in giant anteaters (Myrmecophaga tridactyla Linnaeus, 1758) in captivity. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 15:29-32, 2006. (in Portuguese).

Garcia, J.E., Vilas Boas, L.A., Lemos, M.V.F., de Macedo Lemos, E.G. and Contel, E.P.B.: Identification of microsatellite DNA markers for the giant anteater Myrmecophaga tridactyla. J. Hered. 96:600-6002, 2005.

Griner, L.A.: Pathology of Zoo Animals. Zoological Society of San Diego, San Diego, California, 1983.

Haga, I.R., Martin, S.S., Hosomi, S.T., Vincentini, F., Tanaka, H. and Gatti, M.S.: Identification of a bisegmented double-stranded RNA virus (Picobirnavirus) in faces of giant anteaters (Myrmecophaga tridactyla). Vet. J. 158:234-236, 1999.

Hsu, T.C.: Chromosomes of two species of anteaters. Mammal. Chromosome Newsletter 15:108-109, 1965.

Korniljewa, I.A. and Roshdestwenskaja, I.D.: Zur Zucht des grossen Ameisenbären, Myrmecophaga tridactyla L., im Leningrader Zoopark. Zool. Garten 45:377-384, 1975.

Labruna, M.B., de Paula, C.D., Lima, T.F. and Sana, D.A.: Ticks (Acari:Ixodidae) on wild animals from the Porto-Primavera Hydroelectric power station area, Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 97:1133-1136, Epub 2003 Jan. 20.

Montgomery, G.G., ed.: The Evolution and Ecology of Armadillos, Sloths, and Vermilinguas. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, 1985.

Mossman, H.W.: Vertebrate Fetal Membranes. MacMillan, Houndmills, 1987.

Nowak, R.M.: Walker's Mammals of the World. 6th ed. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1999.

Patzl, M., Schwarzenberger, F., Osmann, C., Bamberg, E. and Bargmann, W.: Monitoring ovarian cycle and pregnancy in a giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla) by faecal progestagen and oestrogen analysis. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 53:209-219, 1998.

Puschmann, W.: Zootierhaltung. Vol. 2, Säugetiere. VEB Deutscher Landwirtschaftsverlag Berlin, 1989.

Schauerte, N.: Untersuchungen zur Zyklus- und Graviditätsdiagnostik beim Grossen Ameisenbären (Mymecophaga tridactyla). (Giessener Elektronische Bibliothek:URN:urn:nbn:de:hebis:26-opus-28121). This is available from: http://geb.uni-giessen.de/geb/volltexte/2006/2812/

Walls, E.W.: Myrmecophaga jubata: An embryo with placenta. J. Anat. 73:311-317, 1939. [Note: M. jubata is synonymous with M. tridactyla - see Wilson & Reeder, 1992].

Wilson D.E. and Reeder, Eds.: Mammal Species of the World. Second Ed. Smithsonian Inst. Press, Washington, 1992.

Wislocki, G.B.: On the placentation of the two-toed anteater (Cyclopes didactylus). Anat. Rec. 39:69-83, 1928.

|