9) Trophoblast external to barrier

There is no extraplacental trophoblast.

10) Endometrium

According to Mossman (1987), "atypical decidua" occurs in Proboscidea but there is no real "decidualization".

11) Various features

Perhaps the most unusual structural feature of elephants aside from tusk and proboscis is the absence of their pleural cavity. Fetuses have a perfectly normal mammalian development but, in the last month of gestation, the lung fuses with the chest wall and mediastinum (Beyer et al.1990). Thereafter, the space is composed of white, elastic connective tissue. Elephants also have no bronchial cartilage and possess no dental nerves. The proboscis is unique and essential for feeding and drinking, as well as for normal social interactions.

12) Endocrinology

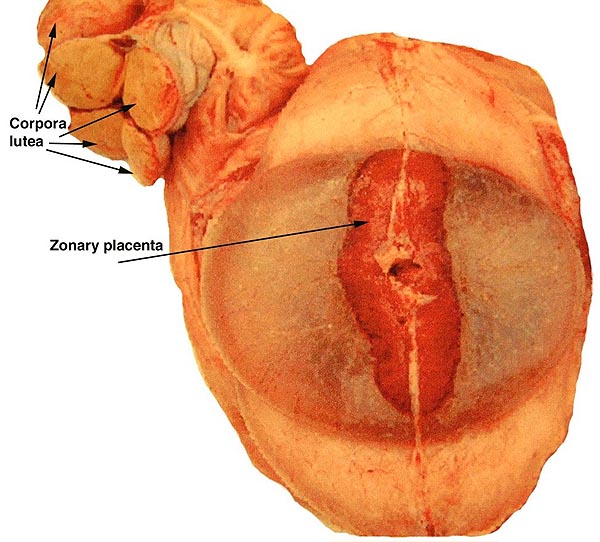

The elephants have a bicornuate uterus with the ovaries being located unusually high in the abdomen (Starck, 1995). There is an ovarian bursa. Accessory corpora lutea develop during gestation. Aside from the paper by Perry (1964), Balke et al. (1988) presented anatomical descriptions of the female reproductive tract, and made reference to other publications. Their data came from 30 elephant culls in Africa and provided measurements, as well as weights.

Schwarzenberger et al. (2001) have presented endocrine data of musth and spermatogenesis in semi-wild Asiatic working elephants. Manual rectal stimulation enabled sperm collection and its evaluation. The review by Flugger et al. (2001) provides some guidance as to progesterone excretion during gestation. It can be ascertained from urine and blood, and appropriate values are given by Niemuller et al. (1993). Other references can be found in the publication by Balke et al. (1988), including semen characteristics. Much recent effort has been spent on sonography and artificial insemination, which is now often successful.

Numerous endocrine studies have been published, beginning with Short's (1966) observation of the ovaries and reproductive tracts of a female elephant. Plotka et al. (1975) determined that progesterone levels rose to 480 pg/ml in pregnancy but estrogen levels were not useful for monitoring. Ramsay et al. (1981), however, felt that urinary estrogen levels were useful with which for following cycles; these occur in approximately 22-day periods. The most recent study comes from Allen et al. (2001) and has been alluded to in section three; it is in abstract form so far only. Hess et al. (1983) also concluded that cycles could be followed by steroid measurements and asserted that progesterone levels fall dramatically prior to parturition. Their findings of a much longer cycle period (16 weeks) were validated by blood steroid level measurements of Brannian et al. (1988). Still other lengths were obtained in the study by Olsen et al. (1994), which suggested that steroid analyses may be useful for management. Pregnancy steroid and prolactin studies were reported by Brown & Lehnhardt (1995). As would be expected from other endocrine studies, Soma and Kawakami (1991) were unable to stain placental sections with antibodies to hCG. Many other studies are referred to that must be studied if further insight is desired. Estrus is 3-4 days.

Graham et al. (2002) developed an enzyme-immunoassay for the measurement of luteinizing hormone in elephants. This is an important advance for the captive breeding and assisted reproductive regimes now practiced in zoo elephants.

Musth in elephant bulls was studied by Ganswindt et al. (2002) by measurements of testosterone and epiandrosterone from urine and feces. There was good correlation of elevated androgen levels with musth and the authors suggested that this correlation may be useful in the management of bull elephants.

It has recently been shown that the common lack of cycling in female elephants is probably the result from hyperprolactinemia (Meyer et al., 2004). When cabergoline was given orally, the prolactin levels fell immediately in one test animal and cycling resumed. The proximate cause for hyperprolactinemia remains unknown.

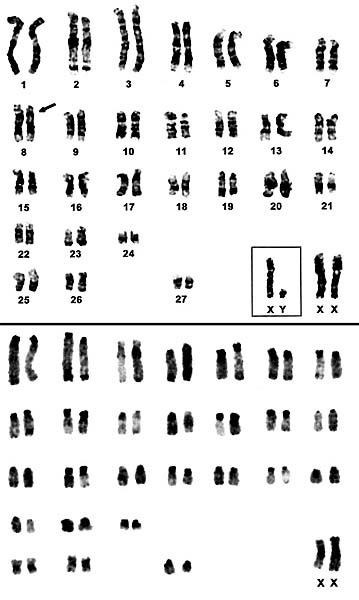

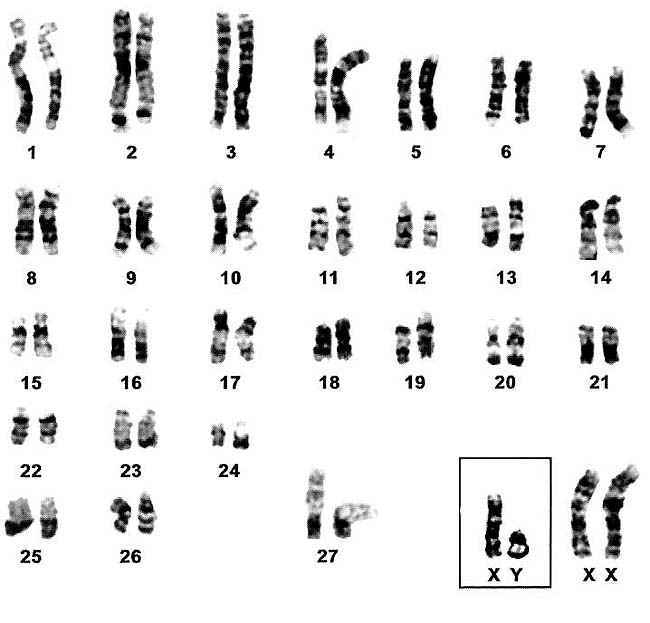

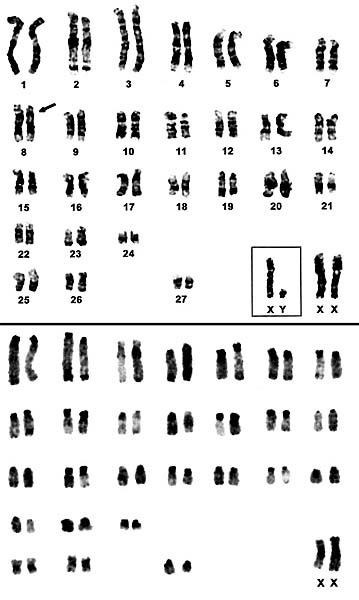

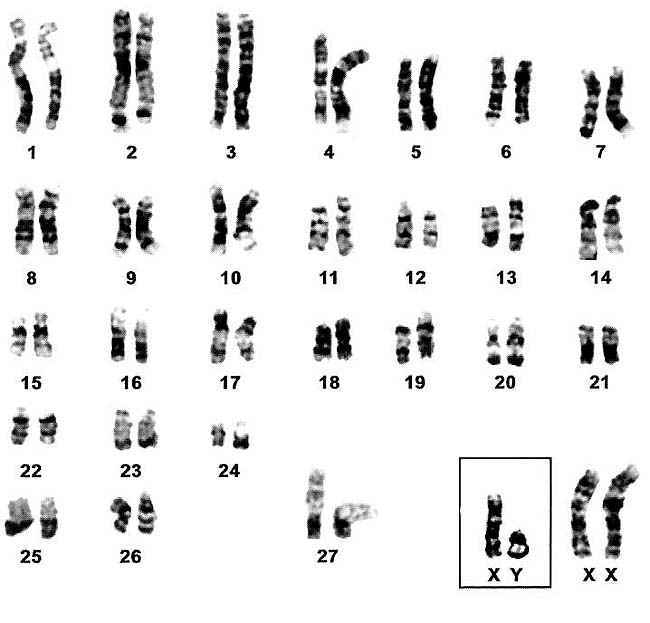

13) Genetics

Both species have the same chromosome number (2n=56), but minor structural differences have been observed in their karyotypes (Houck et al., 2001). Only once has a male hybrid between the two species been recorded, at Chester Zoo. The mother was an Asian elephant, 22 years old. The newborn died in ten days from enterocolitis, weighing 166 lbs. (Howard, 1979). Nevertheless, the ability to hybridize indicates a close genetic relation between the species and very similar reproductive physiologic behavior.

Hartl et al. (1995) showed relatively small genetic diversity by studying proteins and enzyme coding loci in captive Asian elephants, and they also showed minor cytogenetic diversity (C-bands) in eleven individuals studied. Similarly, Fernando et al. (2000) showed only minor genetic diversity with mtDNA studies among 118 free-ranging Asian elephants, and there was little diversity when this was compared with the African species. They suggested this to mean a relatively "slow molecular clock".

|

Karyotypes of male and female African elephants; G-bands above, C-bands below.

|

|

|

|

G-banded karyotype of Asian elephants (Houck et al., 2001).

|

14) Immunology

No studies are known to us.

15) Pathological features

A major problem in captive elephants, especially the Asiatic elephants, has been the infection with an elephant-specific herpes virus from which many animals have succumbed (Richman et al., 1999; Burkhardt et al., 2001; Schaftenaar et al., 2001). The African elephant is considered to be the natural host of this virus and the virus causes only minor disease manifestations in that species. An apparently initially healthy 145 kg neonatal Asiatic bull elephant in Berlin suddenly died from this virus infection at age 268 days, with typical lesions exhibited post mortem. Viral antigen had been demonstrated by PCR in the placenta and in many organs at death. The placenta had shown only some umbilical cord inflammation (Ochs et al., 2001). Genital "papillomatosis" is also reported to be a feature of elephants in captivity.

Tuberculosis presents a significant threat to elephants in captivity (Wohlsein et al., 2001). Both M. hominis and M. bovis have been implicated. Many captive and also some wild elephants suffer tooth disorders, some of which may be life threatening (Fagan et al., 1999a;Wohlsein et al., 2001). Older elephant cows are prone to develop endometrial polyps (hyperplasia) and leiomyomas that limit reproduction. Starck (1995) enumerates the large number of parasites that have been reported in elephants.

16) Physiological data

Aside from their unusual dentition, the trunk and their specialized digestive tract, elephants have normally an obliterated pleural space. Embryos fuse their chest cavity in the last month of gestation (Beyer et al., 1990). The reason for this obliteration has been controversial. Moreover, elephants possess no nerves in their dental pulp (Fagan et al., 1999b). More basic physiologic aspects are discussed by Eltringham (1982).

17) Other resources

Cell strains of animals from both species are available from the cell bank at CRES at the San Diego Zoo by contacting Dr. Oliver Ryder at oryder@ucsd.edu.

18) Other features of interest

Because of the difficulty in accessing the article by Davis & Benirschke (1991), it is reprinted at the very end. It provides more quantitative data. More knowledge of the point of rupture of the umbilical cord would be of interest in future, as well as fetal hormone determination.

References

Aguirre, E.: Evolutionary history of the elephant. Science 164:1366-1376, 1969.

Allen, W.R., Mathias, S., Skidmore, J., Ford, M. and van Aarde, R.J.: Placentation in the African elephant. Placenta 22 (7): abstract P77, page A28, 2001. Reprod. Suppl. 60:105-116, 2002. II.Morphological changes in the uterus and placenta throughout gestation. Placenta 24:598617, 2003.

Amoroso, E.C. and Perry, J.S.: The foetal membranes and placenta of the African elephant (Loxodonta africana) Philosoph. Trans. Roy. Soc. London, Series B. 248:1-34, 1964.

Assheton, R. and Stevens, T.G.: Notes on the structure and the development of the elephant's placenta. Quart. J. Microsc. Sci. 49:1-37, 1905.

Assheton, R.: The morphology of the ungulate placenta, particularly the development of that organ in sheep, and notes upon the placenta of the elephant and hyrax. Philos. Trans. Roy. Soc. Series B, 198:143-220, 1906.

Balke, J.M.E., Boever, W.J., Ellersieck, M.R., Seal, U.S. and Smith, D.A.: Anatomy of the reproductive tract of the female African elephant (Loxodonta africana) with reference to development of techniques for artificial breeding. J. Reprod. Fertil. 84:485-492, 1988.

Beyer, C., Benirschke, K., Wissdorf, H. and Schoon, H.A.: Beitrag zur Problematik der Pleurahöhlenobliteration beim Elefantenfetus (Elephas maximus/Loxodonta africana). Sympos. Erkrank. der Zoo- und Wildtiere. Eskiltuna, Sweden. Akademie Verlag, Berlin. pp. 379-385, 1990.

Brannian, J.D., Griffin, F., Papkoff, H. and Terranova, P.F.: Short and long phases of progesterone secretion during the oestrous cycle of the African elephant (Loxodonta africana). J. Reprod. Fertil. 84:357-365, 1988.

Brown, J.L. and Lehnhardt, J.: Serum and urinary hormones during pregnancy and the peri- and postpartum period in an Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) Zoo Biol. 14:555-564, 1995.

Burkhardt, S., Ehlers, B., Goltz, M. Ochs, A., Wittstatt, U. and Hentschke, J.: Genetic and ultrastructural investigations for detection and classification of the elephant herpesvirus and prophylactic goals. In, Proceedings of the Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, H. Hofer, ed., #4, pp. 157-160, 2001.

Cooper, R.A., Connell, R.S. and Wellings, S.R.: Placenta of the Indian elephant, Elephas indicus. Science 146:410-412, 1964.

Davis, S. and Benirschke, K.: Observations on the placenta of elephants. Sympos. Erkrankungen der Zoo- und Wildtiere, Liberic, CSR, Akademie Verlag, Berlin, pp.39-45, 1991.

Eltringham, S.K.: Elephants. Blandford Mammal Series. Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset, England, 1982.

Fagan, D.A., Oosterhuis, J.E. and Roocroft, A.: Significant dental disease in elephants. Verh. Ber. Erkr. Zootiere 39:15-133, 1999a.

Fagan, D.A., Benirschke, K., Simon, J.H.S. and Roocroft, A.: Elephant dental pulp tissue: Where are the nerves? J. Vet. Dent. 16:169-172, 1999b.

Fernando, P., Pfrender, M.E., Encalada, S.E. and Lande, R.: Mitochondrial DNA variation, phylogeography and population structure of the Asian elephant. Heredity 84:362-372, 2000.

Flugger, M., Goritz, F., Hermes, R., Isenbugel, E., Klarenbeek, W., Schaftenaar, W., Schaller, K. and Strauss, G.: Evaluation of physiological data and veterinary medical experience in 31 Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) births in six zoos. In, Proceedings of the Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, H. Hofer, ed., #4, pp. 123-133, 2001.

Gaeth, A.P., Short, R.V. and Renfree, M.B.: The developing renal, reproductive, and respiratory systems of the African elephant suggest an aquatic ancestry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:5555-5558, 1999.

Ganswindt, A, Heinstermann, M. Borragan, S. AND Hodges, J.K.: Assessment of testicular endocrine function in captive African elephants by measurement of urinary and fecal androgens. Zoo Biol. 21:27-36, 2002.

Graham, L.H., Bolling, J., Miller, G., Pratt-Hawkes, N. and Joseph, S.: Enzyme-immunoassay for the measurement of luteinizing hormone in the serum of African elephants (Loxodonta africana). Zoo Biol. 21:403-408, 2002.

Güßgen, B.: Vergleichende Zusammenstellung der Literaturbefunde über die Anatomie des Indischen und Afrikanischen Elefanten als Grundlage für tierärztliches Handeln. Inaugural Dissertation, Veterinary School, Hannover, Germany, 1988.

Hartl, G.B., Kurt, F., Hemmer, W. and Nadlinger, K.: Electrophoretic and chromosomal variation in captive Asian elephants (Elephas maximus). Zoo Biol. 14:87-95, 1995.

Hatt, J.M. and Liesegang, A.: Nutrition of Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) in captivity - an overview and practical experience. In, Proceedings of the Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, H. Hofer, ed., #4, pp. 117-122, 2001.

Hess, D.L., Schmidt, A.M. and Schmidt, M.J.: Reproductive cycle of the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) in captivity. Biol. Reprod. 28:767-773, 1983.

Hofman, W.: Vergleichend-morphologische Untersuchungen über das Vorkommen elastischer Fasern in den Zottengefäßen von Geburtsplacenten. Acta anat. 66:67-77, 1967.

Houck, M., Kumamoto, A.T., Gallagher, D.S. and K. Benirschke: Comparative cytogenetics of the African elephant (Loxodonta africana) and Asiatic elephant (Elephas maximus). Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 93:249-252, 2001.

Howard, A.L.: "Motty" - birth of an African/Asian elephant at Chester Zoo. Elephant 1:36-41, 1979.

Lang, E.M.: Geburtshilfe bei einem indischen Elefanten. Acta Tropica 20:97-114, 1963.

Ludwig, K.S. and Baur, R.: Zur Struktur der Geburtsplacenta und der unreifen Placenta des afrikanischen Elefanten (Loxodonta africana) Acta Anat. 68:612(abstr.) 1967.

Meyer, J., Ball, R. and Brown, J.L.: Why are so many elephants in captivity not cycling? Evidence of an association between ovarian inactivity and hyperprolactinemia. JEMA (J. of the Elephant Managers Association) 15(1):9-13, 2004.

Mossman, H.W.: Vertebrate Fetal Membranes. MacMillan, Houndmills, 1987.

Niemuller, C.A., Shaw, H.J. and Hodges, J.K.: Non-invasive monitoring of ovarian function in Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) by measurement of urinary 5ß-pregnantriol. J. Reprod. Fertil. 99:617-625, 1993.

Ochs, A., Hildebrandt, T.B., Hentschke, J. and Lange, A.: Birth and hand rearing of an Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) at Berlin zoo - veterinary experiences. In, Proceedings of the Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, H. Hofer, ed., #4, pp. 147-156, 2001.

Olsen, J.H., Chen, C.L., Boules, M.M., Morris, L.S. and Coville, B.R.: Determination of reproductive cyclicity and pregnancy in Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) by rapid radioimmunoassay of serum progesterone. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 25:349-354, 1994.

Perry, J.S.: The structure and development of the reproductive organs of the female African elephant. Philosoph. Trans. Roy. Soc. London, Series B. 248:35-51, 1964.

Plotka, E.D., Seal, U.S., Schobert, E.E. and Schmoller, G.C.: Serum progesterone and estrogens in elephants. Endocrinol. 97:485-487, 1975.

Pucher, H.E., Stremme, C. and Schwarzenberger, F.: Penile paralysis in a semiwild ranging Asian elephant bull (Elephas maximus) in Vietnam - case report. In, Proceedings of the Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, H. Hofer, ed., #4, pp. 177-181, 2001.

Ramsay, E.C., Lasley, B.L. and Stabenfeldt, G.H.: Monitoring the estrous cycle of the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus), using urinary estrogens. Amer. J. Vet. Res. 42:256-260, 1981.

Ramsey, E.M.: The Placenta of Laboratory Animals and Man. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York, 1975.

Richman, L.K., Montali, R.J., Garber, R.L., Kennedy, M.A., Lehnhardt, J., Hildebrandt, T., Schmitt, D., Hardy, D., Alcendor, D.J. and Hayward, G.S.: Novel endotheliotropic herpesviruses fatal for Asian and African elephants. Science 283:1171-1176, 1999.

Schaftenaar, W., Mensink, J.M.C.H., de Boer, A.M., Hildebrandt, T.B. and Fickel, J.: Successful treatment of a subadult Asian elephant bull (Elephas maximus) infected with the endotheliotropic elephant herpes virus. In, Proceedings of the Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, H. Hofer, ed., #4, pp. 141-146, 2001.

Schwarzenberger, F., Pucher, H.E., Stremme, C., Holzmann, A., Tu, N.C. and Ly, C.T.: Endocrinological studies in semi-wild ranging male Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) in Vietnam: Correlation to musth and spermatological parameters. In, Proceedings of the Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, H. Hofer, ed., #4, pp. 135-139, 2001.

Short, R.V.: Oestrous behaviour, ovulation and the formation of the corpus luteum in the African elephant, Loxodonta Africana. East Afr. Wildl. J. 4:56-68, 1966.

Soma, H. and Kawakami, S.: Parturition and placentation in African elephant (Loxodonta africana). Verh. Ber. Erkrank. der Zoo- und Wildtiere. Akademie Verlag, Berlin, pp. 47-51, 1991.

Starck, D.: Lehrbuch der Speziellen Zoologie, Vol. II, part 5/2. Gustav Fischer Verlag, Jena, 1995.

Taylor, V.J. and Poole, T.B.: Captive breeding and infant mortality in Asian elephants: A comparison between twenty Western zoos and three Eastern elephant center. Zoo Biol. 17:311-332, 1998.

Wohlsein, P., Bartmann, C.P., Kirpal, G., Hildebrandt, T. and Peters, M.: Tuberculosis, molar malocclusion and urogenital lesions in a captive Asian elephant (Elephas maximus). In, Proceedings of the Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, H. Hofer, ed., #4, pp. 161-171, 2001.

Because of the difficulty in accessing this article, it is here reprinted in full.

OBSERVATIONS ON THE PIACENTA OF ELEPHANTS

University of California and the San Diego Zoo, San Diego, California

By S. Davis and K. Benirschke

(Citation: Davis S. and Benirschke, K. Observations on the placenta of elephants. Symposium on Erkrankungen der Zoo- und Wildtiere. Liberic, CSR. Akademie Verlag, Berlin, pp. 39-45,1991).

Introduction

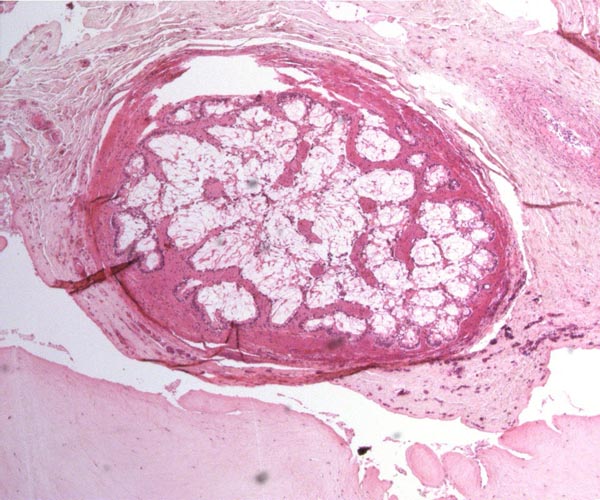

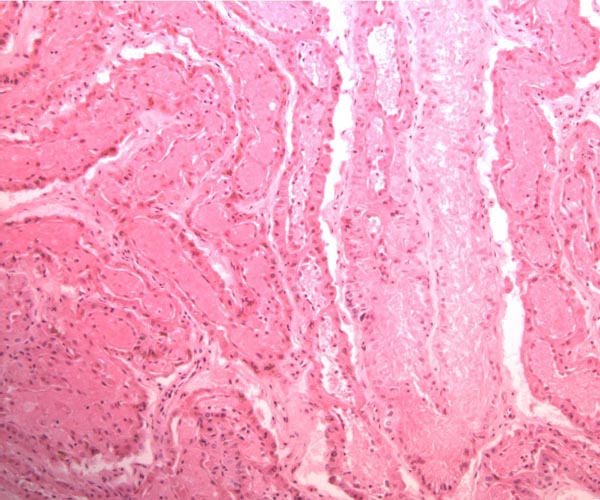

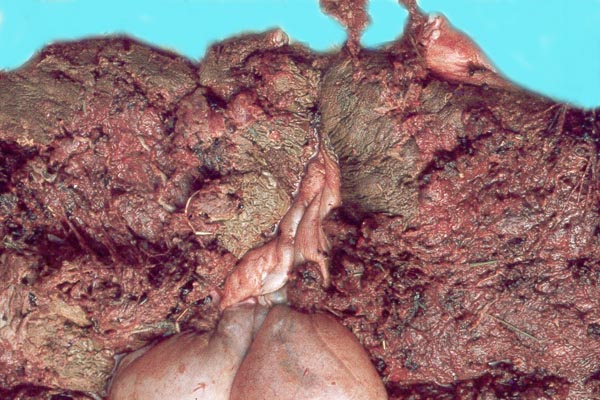

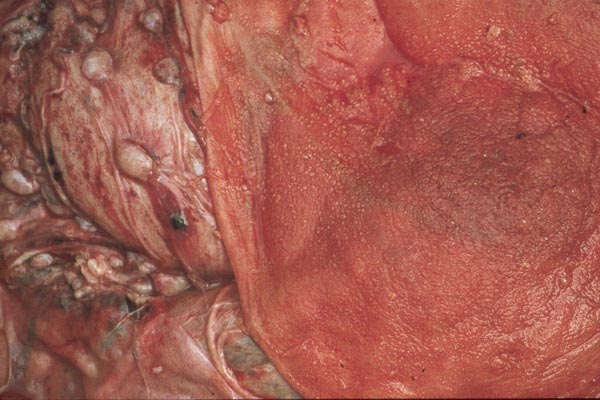

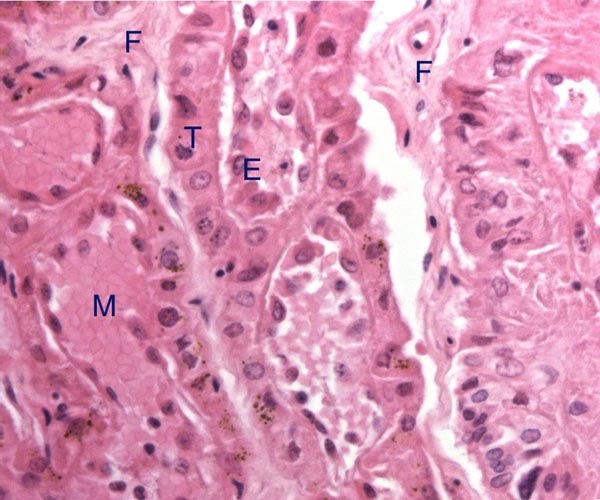

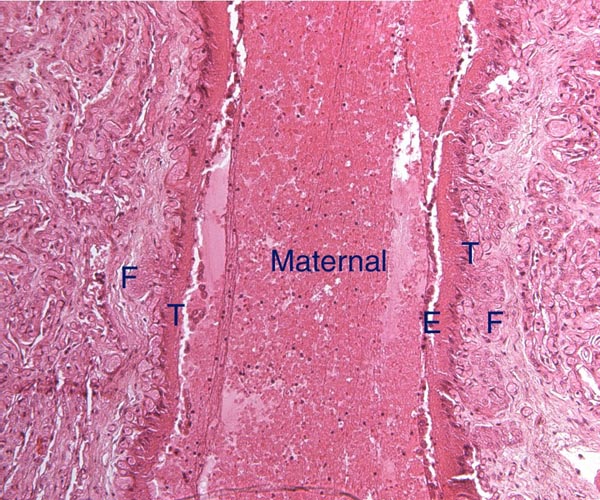

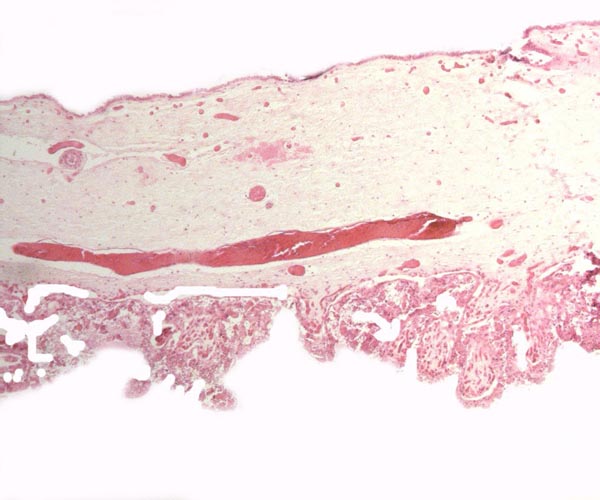

The placenta of elephants has not often been studied, and delivered specimens from mature Asian elephants have only been described by COOPER at al. (1964). Especially lacking are studies that compare the placentas of the two species with one another. The most detailed report of implanted specimens from African elephants at various gestational ages comes from the pen of AMOROSO and PERRY (1964). These authors had incomparably fixed uteri and made precise descriptions of the various structures they identified in the elephant placenta. They preferred to call the type of placentation in this species as being "vasochorial", rather than the conventional "endotheliochorial" type. In his comprehensive book on the placentas of all mammals, MOSSMAN (1987) considered the elephant placenta as belonging to the "hyracoid type", as being incompletely zonary, labyrinthine and endotheliochorial, with large allantoic sac, small marginal hematoma, and with accessory villous areas over an otherwise smooth allantois. His drawings suggest that the allantoic sac extends into the empty uterine horn and that the free amnio-allantoic membrane contains fetal blood vessels. MOSSMAN (1987) also pointed out that the similarity of the elephant placenta to that of carnivores (initially suggested by the zonary shape and marginal apparent hematomas) is incorrect. The placenta of elephants, however, is believed to have great similarity to that of the hyrax and manatee in that all have fourlobed allantoic sacs, amnionic and allantoic verrucae (often called pustules), and short umbilical cords in which veins and arteries were alluded to as being paired. AMOROSO and PERRY (1964) found no evidence to suggest that the zonary shape of the placenta results from atrophy of portions of a formerly diffuse placenta. They could not affirm the presence of minor villous projections on the free membranes, findings that are in agreement with ours.

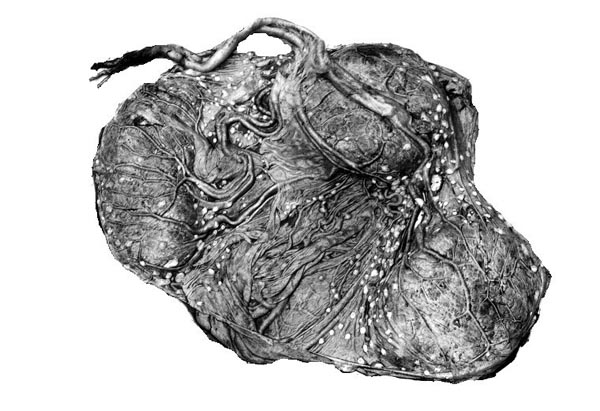

At San Diego Zoo's Wild Animal Park groups of female African and Asian elephants have been kept and, in recent years, males of both species have been acquired. Since then, five African and three Asian elephants have been born, in addition to an abortus of an Asian elephant. The placentas were obtained from all within few hours after delivery. They were weighed, measured and gross observations were recorded. Many photographs were taken. Histologic sections of defined areas of placenta, membranes and umbilical cord were prepared. These findings represent the substance of this report.

Observations

The principal macroscopic findings are summarized in Table I and a brief description is given here of the individual cases.

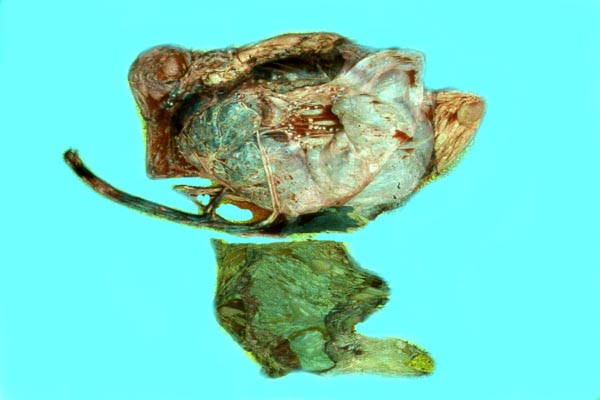

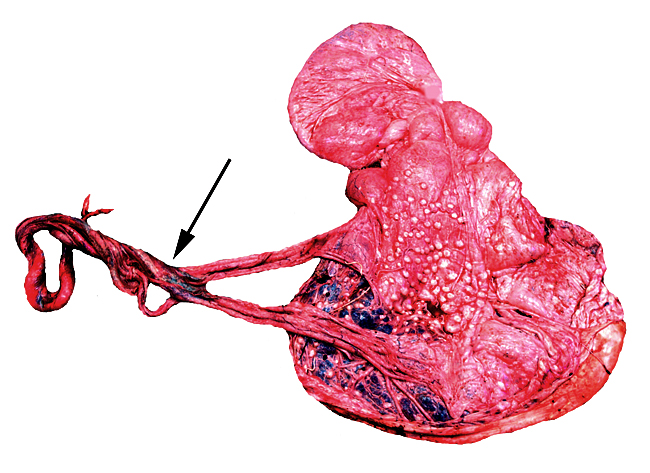

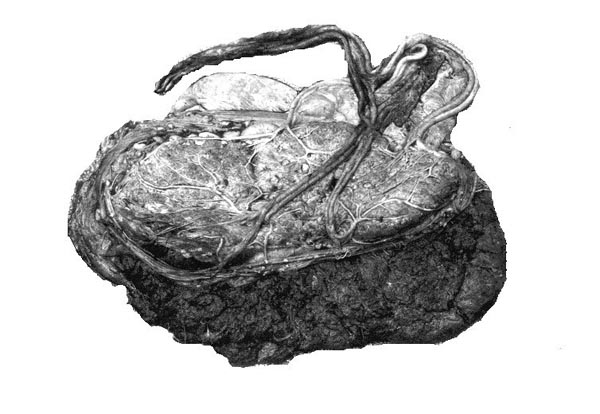

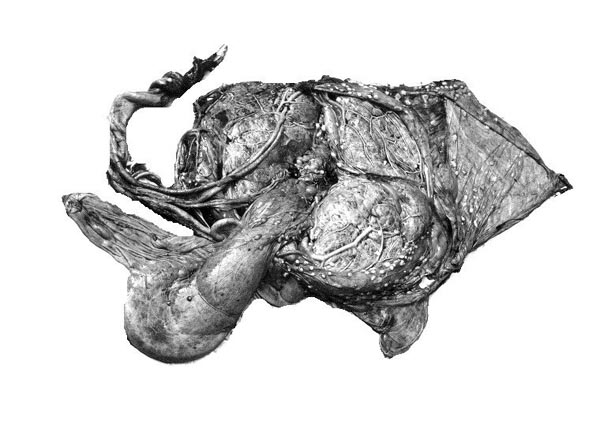

Case 1. The umbilical cord was 59 am long with three vessels. It divided into three portions at this point, measuring 4,B, 49 and 66 cm respectively until these entered the placenta at the margin (Fig. 1). Thus the total cord length was 125 cm (The length of all the umbilical cords was calculated as the longest distance from cord rupture site to the entry of the cord into the placental bed). The placenta had two large lobes, separated by 68 cm of membranes. The lobes measured 70 x 28 x 6 cm and 62 x 22 x 1O cm. A marginal hematoma and green staining of the membranes was noted. Many allantoic pustules were present. The 95.5 kg infant was gored by an adult female at age 4 days and died one week later.

Case 2. The total length of umbilical cord was 112 cm. The placenta had two lobes weighing 5,500 and 3,200 g respectively. The margins of the placenta had the usual hematoma, and allantoic pustules were present. Delivery of the calf was not observed, thus the dam had eaten approximately half of the placenta prior to examination.

Case 3. The placenta of this 13 year old African elephant was ring-shaped, composed of three separate lobes and weighed 22.2.kg. The lobes measured 44 x 26 cm and 44 x 28 x 4 cm. There was a green marginal hematoma, measuring up to 0.3 cm in thickness. The allantois was covered with pustules. The cord measured 65 cm in length. It had three vessels, but 43 cm from the torn end, one vessel branched. The cord also contained a huge allantoic duct and measured 6 cm in diameter. Pustules and hematoma of the spontaneously ruptured umbilical cord are shown in Figure 2. The mother had been immobilized several times during pregnancy for surgical repair of a broken leg.

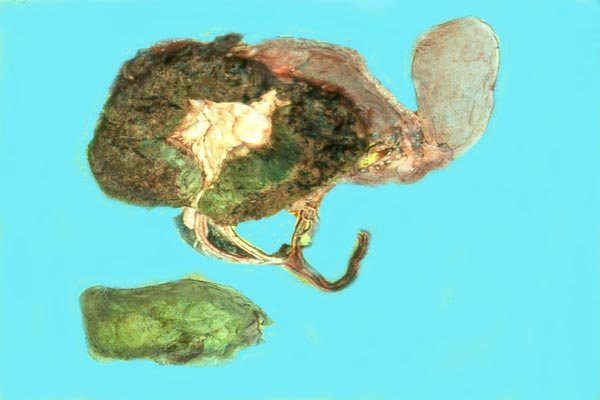

Case 4. The umbilical cord inserted in almost marginal fashion and measured 65 cm. The vascular division began approximately 30 cm from its fetal end. It contained a large allantoic duct and three vessels. Abundant pustules were present on the membranes (Fig. 3). The placenta weighed 13.45 kg. There were three lobes measuring 34 x 35 x 5 cm, 31 x 41 x 4 cm, and 47 x 22 x 4.5 cm, weighing 6,000, 4,250 and 3,200 g respectively. A marginal hematoma was present, measuring up to 1 cm in thickness.

Case 5. The umbilical cord of this 11 year old African elephant's baby was 100 cm long, possessed three blood vessels and large allantoic duct. Its fetal end had much hemorrhage. The placenta was ring-shaped but had 3 ovoid lobes and weighed 17.6 kg. Relatively few pustules were observed in this specimen; there was a marginal hematoma at the edge of all three lobes.

Case 6. The umbilical cord measures 50 cm in length and the four fused lobes of placenta, which had a generally annular shape, weighed 8.3 kg. Its thickness was 5 cm. There were no pustules on its shiny surface. A marginal hematoma was present. The membranes which were weighed separately, were 1,350 g. The cord weighed 750 g and, approximately 9 cm from its fetal end, the vein divided and 13 cm further, another branching took place. Eventually, four artery/vein pairs entered the placental surface.

Case 7. The placenta of this stillborn calf weighed 1,100 g with its attached 23 cm long cord. The latter had three twists and contained 2 arteries and one vein, as well an allantoic duct that funneled into the allantoic cavity. The allantoic sac was covered with brown pustules in its center, varying in size up to 2 cm and 0.2 cm in thickness. They disappeared towards the edge of the placenta. There was no marginal hematoma. Histologically, this placenta was markedly different from the others. Its blood vessels contained calcified former thrombi and these extended deeply into the placental tissue. The maternal vessels had much more recently developed thrombi and the interdigitation of maternal and fetal tissues was very evident. Moreover, the uterine epithelium had not atrophied to produce a vaso-chorial placenta, and the trophoblastic coverings of the fetal placental trabeculae (lamellae) was degenerated.

Case 8. This placenta was delivered at Cesarean section from a 19 year old nulliparous Asian elephant. The dam had a 744 day gestation based on observed copulation and subsequent rise in progesterone. A progesterone level 76 days prior to delivery had fallen to baseline. It was determined that the calf had died and a decision was made to perform a Cesarean section to attempt to salvage the dam. The placenta weighed 11.16 kg, and the membranes 2.12 kg. The umbilical cord was 82 cm long and 4 cm thick. The annular placenta measured 14 x 34 x 3 cm.

Case 9. This stillborn' a placenta weighed 14.5 kg. The dam had ruptured the membranes 5 days prior to delivery of a large stillborn calf.

|